What are iPSCs?

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) are stem cells generated by reprogramming somatic (adult) cells to return to a pluripotent state. They possess similar attributes to embryonic stem cells (ESCs).

Human iPSCs (hiPSCs) can be differentiated into virtually any cell type found in the human body, using specific growth factors, cytokines, and substrates into mature cells.

Differentiation of hiPSCs compiles a series of steps that mimic tissue and organ formation during embryonic stages.

The Process of Differentiation

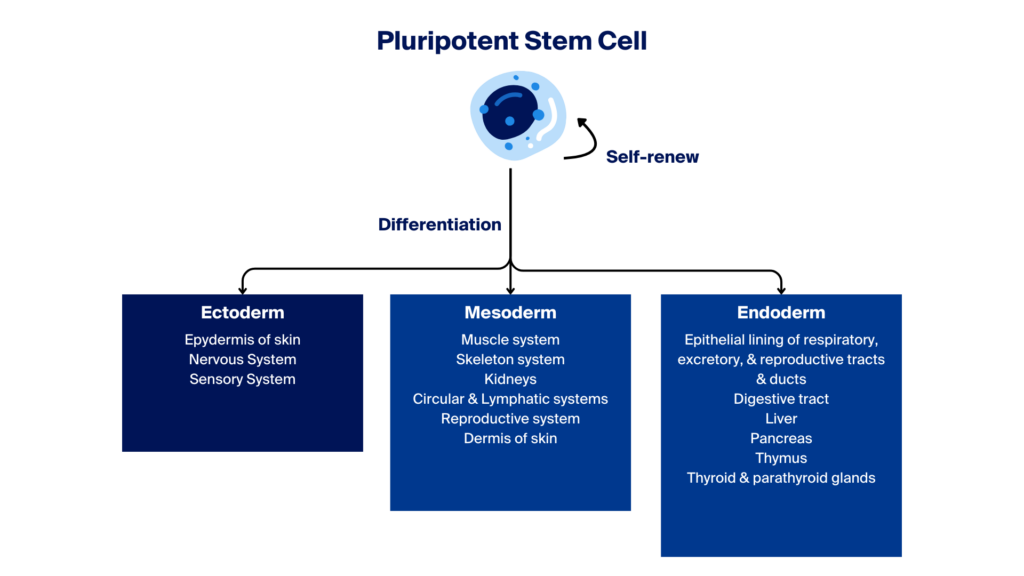

Newly formed pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) have the potential to differentiate into one of three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm—which can further develop into intermediate or terminally differentiated specialised cells.

Differentiation refers to the processes or stages in which iPSCs abandon their pluripotent stage and become committed to line-specific adult-like cell types, which can potentially be used in research and clinical applications.

What Influences iPSC Differentiation?

Various external factors must influence iPSCs’ change for them to successfully undergo the various stages of differentiation.

Growth Factors and Cytokines

Growth factors and cytokines are used as signalling molecules that govern the fate of iPSCs directing them along developmental trajectories.

Growth factors such as BMPs, FGFs, and Wnts orchestrate the activation of specific signalling pathways and the expression of lineage-specific genes.

Cytokines influence the behaviour of iPSCs, although not all differentiation processes depend on these external factors for successful specialisation. For instance, interleukin-6 (IL-6) can influence the differentiation of iPSCs into certain immune cells, demonstrating the specific effects of cytokines in stem cell biology.

3D Culture Systems and Organoids

3D culture systems and organoids offer a physical and structural advantage in replicating in vivo conditions and, in some cases, can enhance the efficiency of iPSC differentiation.

Unlike traditional 2D cultures, these three-dimensional environments provide iPSCs with spatial cues and interactions that more closely mimic native tissues. This fosters accurate differentiation and encourages the formation of complex tissue structures formed by two or more cell types, enabling the study of organ-specific functions and diseases.

Co-culture Techniques

Co-culture techniques involve growing iPSCs in the presence of other cell types or within a specific cellular microenvironment.

In some co-culture systems, iPSCs are grown directly with other specific cell types to promote differentiation. This approach aims to mimic the natural cellular interactions and signals in the body, enhancing the differentiation, maturation, and functionality of the iPSC-derived cells. On the other hand, when co-cultures involve cell types from different organs, removing the nurturing cell type component is necessary if cells are intended for functional studies or clinical use.

Differentiation into Key Lineages

IPSC differentiation aims to transform iPSCs into specific, functional cell types. This differentiation is essential for advancing regenerative medicine, disease modelling, and drug discovery. The lineages described below are highlighted due to their broad applications and significant impact in current research and therapy development. However, it’s important to note that other lineages, such as lymphopoietic lineages which are crucial for producing allogeneic CAR T cells, also play critical roles in medical science.

Neural Lineages – Initially, hiPSCs are guided to adopt an ectodermal fate, the germ layer from which the nervous system originates. Subsequently, they can be coaxed into neural progenitor cells and further differentiated into mature neurons, astrocytes and glial cells.

Cardiovascular Lineages – The differentiation of hiPSCs into cardiovascular lineages, including cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts, involves sequential steps that lead hiPSCs towards a mesodermal fate, the precursor to heart cells. Activation of specific cardiac transcription factors eventually yields functional components of the cardiovascular system.

Hematopoietic Lineages – hiPSCs can be differentiated into various blood cell types, such as erythrocytes, platelets, and immune cells, mimicking the hematopoietic lineage. The process commences with hiPSCs adopting a mesodermal fate and progressing towards hemangioblasts, common precursors for endothelial and blood cells.

Endodermal Lineages – hiPSCs can be directed towards endodermal lineages to generate cell types found in internal organs like the liver and pancreas. The result is the production of functional hepatocytes, pancreatic beta cells, and other organ-specific cell types.

Mesenchymal Lineages—Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from hiPSCs are developed by guiding iPSCs towards a mesodermal fate. These cells can differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. iPSC-derived MSCs provide a potentially unlimited supply for both autologous and allogeneic cell therapies, overcoming the limitations of donor-derived MSCs.

Challenges and Limitations in iPSC Differentiation

Although the differentiation of hiPSCs into various cell types holds tremendous potential for regenerative medicine, disease modelling, and drug discovery, the processes involved in iPSC differentiation face several challenges and limitations that researchers are actively working to overcome.

Ensuring the Purity of Cell Populations

One of the foremost challenges in iPSC differentiation is ensuring the purity of the resulting cell populations.

Although iPSCs possess the remarkable capacity to differentiate into various cell types, this pluripotency can lead to a heterogeneous mix of cells. Researchers face the intricate task of refining differentiation protocols to obtain homogenous populations of desired cells while minimising the presence of off-target cell types.

This complexity necessitates constantly optimising differentiation protocols and novel cell sorting and enrichment techniques.

Recapitulating in vivo Development

Another significant challenge is replicating the conditions and timelines of natural human development in vitro.

In vivo development is a finely tuned process influenced by a multitude of factors, including spatial and temporal cues, signalling pathways, and epigenetic modifications. Recreating these intricate dynamics in a culture dish is a formidable task.

Researchers must develop precise differentiation protocols that mimic the in vivo microenvironment to accurately guide iPSCs toward the desired cell fate.

Functional Validation

Beyond appearances, it is vital to ensure that the differentiated cells do not merely look the part but also function effectively and safely when transplanted.

Functional validation is a critical aspect of iPSC differentiation. Researchers need to assess differentiated cells’ functionality, maturity, and stability through rigorous quality control measures and functional assays, thus ensuring that iPSC-derived cells can perform their intended roles in therapeutic applications or disease modelling.

The Future: Advancements in Differentiation Protocols

With induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research moving rapidly, researchers are actively exploring innovative approaches and leveraging cutting-edge technologies to develop more efficient, scalable, and precise differentiation processes.

Advanced cell culture systems represent a significant avenue of progress. Researchers are working to enhance culture substrates, employ three-dimensional (3D) culture techniques, and use microfluidic systems to better mimic the native microenvironment of developing tissues and organs.

Gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9, are also crucial in shaping the future of iPSC differentiation. These tools enable precise manipulation of iPSCs’ genetic makeup, guiding them toward specific lineages and allowing researchers to optimise differentiation protocols, minimising the occurrence of off-target cell types.

Small molecules and signalling pathway modulators are increasingly critical in directing cell fate during differentiation. Researchers are using these chemical tools to exert precise control over cellular processes, enabling the greater accuracy of generating homogeneous populations of desired cell types.

Machine learning algorithms and computational biology are helping to analyse extensive datasets generated from techniques like single-cell RNA sequencing. This data-driven approach helps uncover novel insights into differentiation processes, assisting researchers in refining protocols and identifying critical regulators of cell fate.

Combined with advancements in automation and scale-up techniques, they are pivotal for translating iPSC differentiation protocols into clinical applications. Scalable bioreactors and automated systems enable the production of large quantities of differentiated cells, a crucial aspect for therapies and drug screening on a larger scale.

Conclusion

The differentiation journey in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is central to realising their immense therapeutic potential.

With ongoing research and technological advancements, iPSC differentiation is set to achieve more efficient, precise, and scalable differentiation protocols. These developments are poised to revolutionise how we approach various medical conditions and create unprecedented opportunities for personalised medicine.

At NecstGen, we are actively working in the field of iPSC research. To learn how we can help with your development or manufacturing of stem cell and gene therapies, reach out to discuss your challenges.